Dreams of sea adventures, the feeling of complete freedom under sail, quality time spent with family and friends away from the daily hustle and bustle, entice many. It's not just a vacation; it's an opportunity to reset, to find yourself in a new, boundless element. However, this dream often collides with fears: sailing seems incredibly complex, accessible only to a select few, and training will take years and cost a fortune. Confusion in certification systems and potential language barriers in international schools can also pose serious obstacles.

This is where GPS – the Global Positioning System – comes to the rescue. It's not just a technology; it's a symbol of accessibility and reliability in modern sailing. Just as GPS made navigation accessible to millions of smartphone users, it has also simplified learning to sail. Understanding how GPS works and how it integrates with other Navigation systems helps to dispel many myths about the complexity of sea voyages. Without understanding modern navigation tools and without proper training, one can miss out on the incredible opportunities that the world of sailing opens up. If even such a complex and potentially dangerous field as maritime navigation has become significantly safer thanks to GPS, then the learning process at a sailing school that emphasizes modern methods and safety will be reliable and trustworthy.

The History of GPS: How a Military Secret Became Our Guide

The history of GPS, or Global Positioning System, began as a secret military development of the United States. Initially, this technology was intended for high-precision missile guidance, tracking military objects, and providing navigation for the armed forces. Parallel to the American system, the Soviet Union developed its analogue – GLONASS, which also had a military origin.

Over time, thanks to technological development and changes in the geopolitical situation, this development moved beyond exclusively military use and became an integral part of civilian life. However, to maintain high precision advantage for the military, a "limited access" mode, known as Selective Availability (SA), was introduced in March 1990. This mode artificially reduced the accuracy of civilian GPS, making it less suitable for high-precision tasks.

A key moment for civilian users was the historic decision by US President Bill Clinton on May 1, 2000, to disable SA mode. This event fundamentally increased the accuracy of civilian GPS, making it suitable for a wide range of applications, including maritime navigation. This was not just a technical change, but a political decision that opened a new era in navigation and significantly enhanced the safety, convenience, and accessibility of sea travel for everyone. In September 2007, a final decision was made to produce future GPS satellites (GPS III) without SA function, cementing the policy of open and accurate access to GPS for civilian users on a permanent basis.

The history of GPS is a vivid example of how technologies created for military purposes can be "democratized" and transform civil spheres. The abolition of Selective Availability became a powerful driver of progress that directly influenced everyday hobbies such as yachting. This fact also emphasizes that even the most common and "free" technologies can be subject to government-level decisions, which logically leads to the idea of needing alternative navigation methods, which will be discussed later in the article as part of a skipper's comprehensive training. For successful maritime navigation, it is crucial to use all available tools.

How GPS Works: Easy to Understand, Priceless to Use

GPS is a satellite radionavigation system based on measuring distances to satellites. Behind the apparent simplicity of using GPS lies a colossal, high-precision global infrastructure that requires constant monitoring, correction, and maintenance. Understanding this complexity increases the value of the technology and at the same time emphasizes why it is important not to rely on it blindly, even knowing how GPS works.

The GPS system consists of three main segments:

- Space Segment is the "heart" of the system. This is an orbital constellation consisting of a minimum of 24 (currently 31) satellites orbiting the Earth at a medium Earth orbit, approximately 20,200 kilometers high. Each satellite continuously transmits radio signals containing precise information about its location and transmission time.

- Control Segment is the "brain" of the system. It includes the Master Control Station located in Colorado Springs, as well as a network of monitoring stations and ground antennas distributed around the world. These stations track all visible GPS satellites, collect range data, calculate their precise orbits, and generate updated navigation messages. These messages are then transmitted to the satellites so they can broadcast them to users.

- User Segment is the "hands" of the system, meaning our GPS receivers. These can be devices built into smartphones, tablets, marine chartplotters, or specialized navigators.

Receivers receive signals from satellites, process them, and calculate their precise three-dimensional position (latitude, longitude, altitude), as well as precise time. The main principle of GPS operation is based on trilateration. The receiver determines the distance to each satellite by measuring the time it takes for a radio signal to travel from the satellite to the receiver. Since the speed of the radio signal is known (it's the speed of light), the distance is easily calculated. Imagine you're drawing circles on a map: each satellite is the center of a circle, and the radius of the circle is the measured distance to the satellite. The intersection of two such circles gives two possible locations. The intersection of three circles allows you to determine your location on the Earth's surface. To determine the three-dimensional position (including altitude) and precise time, a signal from at least four satellites is required.

To better understand the principle of trilateration, imagine three people standing around a lake, each holding one end of a string, with the other end tied to a rubber duck. Knowing the precise length of each of these three strings, one can very accurately determine the exact and unique position of the duck within this circle. In this metaphor, the "string length" represents the time it takes for a signal to travel from a GPS satellite to your receiver. Just as knowing the string lengths from three people allows you to determine the duck's location, knowing the signal travel time from at least three satellites allows the GPS device's software to accurately calculate your unique position on Earth at a given moment in time. This calculation can be repeated a second later to determine a new position, which then allows the device to report speed and direction.

A key element of GPS operation is the incredibly precise measurement of signal travel time. Satellites are equipped with atomic clocks, and receivers measure tiny delays. This reliance on time links modern satellite navigation with historical milestones in maritime navigation, such as the invention of the accurate chronometer in the 18th century, which allowed sailors to determine longitude with high precision. This connection between "new" and "old" shows that Sailing Training involves understanding not just "how to push a button," but also "how it works," which makes a skipper more competent and confident.

GPS on Board (Sailboat): From Smartphone to Professional Chartplotter

GPS has become so ubiquitous that today, a modern sailboat usually has several devices equipped with GPS receivers: from built-in chartplotters to smartphones and tablets. This significantly improves electronic navigation for sailing. GPS receivers come in different types: fixed, integrated into marine navigation systems, and portable, such as smartphones or smartwatches.

The presence of GPS in every smartphone creates a false impression among beginners that "a phone is all you need." However, a detailed comparison with marine instruments shows that "consumer" technology, though convenient, lacks the necessary reliability, autonomy, and functionality for professional or even serious recreational sailing. This highlights that "accessibility" of technology doesn't always mean "readiness for marine conditions."

Comparison of GPS in phones and marine navigation instruments

| Parameter | GPS in a Phone | Marine Chartplotter |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Typical (4.9–10 m) | High (5–10 m, with corrections down to cm) |

| Reliability | Low (not waterproof, fragile) | High (waterproof, impact-resistant) |

| Autonomy (battery life) | Low (4 hours of active GPS use) | High (days/weeks) |

| Integration with onboard systems | None (only via third-party apps) | Full (radar, echo sounder, AIS, autopilot) |

| Screen readability | Low/Medium (in sunlight, with wet/gloved hands) | High (in bright sunlight, with wet/gloved hands) |

| Primary purpose | Auxiliary navigation/Backup | Main navigation |

| Cost | Low | High |

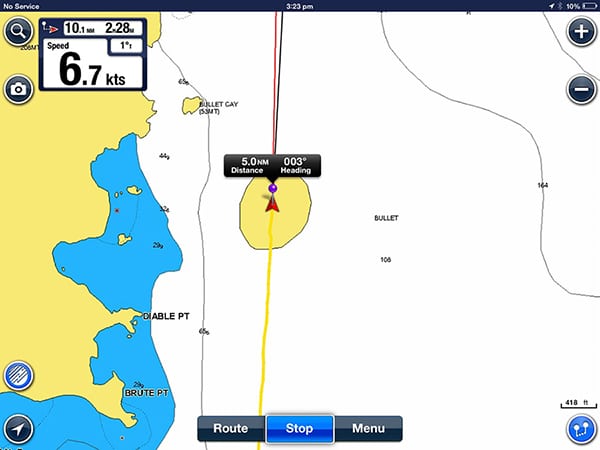

From the table, it is clear that marine navigators (chartplotters) are designed specifically for harsh marine conditions. They are waterproof, shock-resistant, and resistant to saltwater and vibrations. Professional navigators have significantly lower power consumption compared to smartphones, which is critical for long voyages where access to charging is limited. They are often part of a comprehensive onboard navigation system, integrated with radar, depth sounder, AIS (Automatic Identification System), and other sensors, providing the skipper with a complete navigational picture on one screen. Chartplotter screens are equipped with special coatings that are easily readable in bright sunlight, do not glare, and respond correctly to touches even with wet hands or gloves. This ensures reliable GPS operation on board.

Smartphones, while convenient and always at hand, have significant drawbacks: high power consumption with active GPS (battery can die in 4 hours), vulnerability to moisture, dirt, dust, and touchscreen issues when wet. They are excellent as a supplementary tool or backup option, but should not be the primary navigation device for serious sailing.

What is A-GPS (Assisted GPS) and why is it important

A-GPS (Assisted GPS) is a technology developed to improve the performance of conventional GPS, especially in challenging conditions where the satellite signal is weak or blocked (e.g., surrounded by tall buildings, indoors, under dense tree cover). A-GPS uses data about the current state of satellites and their location, which are transmitted via cellular towers (terrestrial channels). An assisting server tells your phone where the nearest satellites are, thereby reducing the time it takes to find them.

Advantages of A-GPS include:

- Fast "cold start": Significantly reduces the time required for the first position fix (Time To First Fix, TTFF), as the receiver does not need to independently download all orbital information from satellites.

- Improved accuracy in challenging conditions: Helps the GPS receiver better interpret weak signals, which increases positioning accuracy in poor reception conditions.

- Battery saving: By speeding up the location determination process, A-GPS reduces the power consumption of the GPS module, as it spends less time actively searching for signals.

For sailing in the open sea, where there is no cellular connection, A-GPS is irrelevant. However, when approaching shore, in marinas, or in urban canals where the satellite signal may be weak, A-GPS in a smartphone or tablet can be very useful for quickly and accurately determining location. The identified disadvantages of smartphones (power consumption, water vulnerability) highlight the critical need for reliability and autonomy at sea. This leads to the conclusion that a sailboat should always have backup navigation systems (e.g., a full-fledged chartplotter and a smartphone as a backup) and a comprehensive approach to their use. This is directly related to the safety and training of the skipper, who must be prepared for any scenario, not relying on a single device.

Alternatives to GPS: Navigation in Any Conditions

Despite the dominance of GPS, it is not the only global navigation system. There are other global navigation satellite systems (GNSS), as well as traditional navigation methods, which remain relevant and even critically important under certain conditions.

Overview of global navigation satellite systems (GNSS), including the global positioning system

| System | Country of Origin | Number of Satellites | Civilian Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPS | USA | 31 | 5–10 m |

| GLONASS | USSR/Russia | 24 | 4.5–7.5 m |

| Galileo | EU | 24 | up to 1 cm (commercial) |

| BeiDou | China | 35 | 2.5–5 m |

Modern navigation devices often support receiving signals from several GNSS simultaneously (e.g., GPS + GLONASS + Galileo). This significantly increases the accuracy and reliability of positioning, especially in challenging conditions where the visibility of satellites from one system may be limited.

Traditional navigation methods: why they are still relevant

The availability of multiple GNSS and, even more importantly, proficiency in traditional navigation methods, is not just "desirable" but critically important for ensuring safety at sea. These are not simply "old" methods, but necessary, time-tested backup systems that do not depend on electronics and can be used in case of interference, equipment failure, or other unforeseen situations.

- Compass: Remains the primary and most reliable navigation tool for determining direction of travel. It serves as an indispensable backup to GPS in case of electronic equipment failure.

- Nautical Charts (paper): Having an up-to-date set of paper charts on board is the most important condition for minimizing potential risks. Paper charts still outperform electronic displays in terms of speed of scanning a large area and information density. They are critically important for route planning and as a backup.

- Chronometer: Historically was a key tool that allowed for high-precision time determination and, consequently, longitude calculation. Its principle remains the basis of modern navigation.

- Radar: Indispensable for detecting other vessels, buoys, and potential hazards in conditions of poor visibility (fog, rain, night). Modern radars are often integrated with GPS to increase accuracy.

- AIS (Automatic Identification System): Transmits and receives information about other vessels (their identification, position, course, speed) equipped with AIS, significantly enhancing maritime safety and reducing the risk of collision, especially in busy areas.

- EPIRB (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon) and PLB (Personal Locator Beacon): Emergency radio beacons used to transmit a distress signal in case of an accident. They transmit a signal that is received by satellites, allowing rescuers to quickly locate the vessel.

- Visual bearings and dead reckoning: Skills in determining a vessel's position by shore landmarks (lighthouses, capes) and calculating the distance traveled based on course and speed. These basic skills are necessary for verifying electronic readings and for navigation in case of GPS failure.

Including an extensive section on traditional navigation methods alongside modern GNSS emphasizes that navigation is not just a technical skill of "pressing a button," but an art that requires a deep understanding of the environment, the ability to read charts, work with a compass, observe the sea and sky. This makes the learning process deeper, more interesting, and multifaceted, rather than just a software usage course. For beginners, this means that sailing training is not only about mastering modern gadgets but also understanding fundamental principles that will not fail for safe maritime navigation.

GPS Accuracy and Signal Challenges: Interference and High Latitudes

Although GPS is a highly accurate tool, its precision is not absolute and can vary. A typical GPS smartphone has an accuracy of up to 4.9 meters, while high-quality marine GPS devices provide accuracy within 5-10 meters under normal conditions. With differential corrections (DGPS, RTK), accuracy can reach centimeters.

Several factors influence GPS accuracy:

- Number and geometry of satellites: The more satellites the receiver "sees" and the better their spatial arrangement (geometry), the more accurate the calculation. For three-dimensional positioning, a minimum of four satellites is required.

- Atmospheric conditions: GPS signals pass through the ionosphere and troposphere, where delays and distortions (refraction) can occur, affecting accuracy.

- Signal blockage: Tall buildings (in cities), dense forests, or mountains can partially or completely block signals from satellites, reducing their number and worsening geometry.

- Multipath propagation: This is one of the main causes of errors. Signals from satellites can reflect off surfaces (buildings, rocks, water, the sailboat itself) before reaching the receiver. The receiver receives multiple copies of the same signal with slight delays, leading to inaccuracies in positioning (error can be several meters).

GPS jamming and spoofing: A new threat at sea

Despite its apparent reliability, GPS is not an infallible tool and is subject to many external influences – from atmospheric phenomena to deliberate interference.

- Jamming: This is deliberate radio frequency interference where a powerful signal drowns out or "floods" weak GPS signals from satellites. As a result, the GPS receiver loses the signal and cannot determine location. Jammers can be local and create significant navigation problems.

- Spoofing: This is a more sophisticated and dangerous threat. Spoofing involves transmitting false GPS signals that deceive the receiver, making it "think" it is in a completely different location. This can lead to serious navigational errors, deviations from course, and even collisions. For example, vessels in the Black Sea have encountered situations where their GPS showed them to be on land tens of kilometers from their actual location.

The consequences of GPS jamming and spoofing for maritime navigation are significant: they increase the risk of accidents, can cause delays, lead to route deviations, missed ports, and create threats to the safety of crew and cargo. In regions of geopolitical conflict (e.g., Baltic Sea, Black Sea, Red Sea), such incidents are becoming more frequent. It is important to pay attention to discrepancies between GPS readings and other navigation instruments (radar, AIS) or visual observations. Sudden jumps in GPS position or speed are an alarming sign. In case of interference, the skipper should switch to traditional navigation methods (dead reckoning, visual bearings, radar), increase distance to other vessels, and consider entering port during daylight hours.

Peculiarities of GPS operation in high latitudes

GPS performance begins to degrade above 55° latitude. This is due to the orbital geometry of GPS satellites. In polar regions and high latitudes, the GPS signal is less stable and less accurate. GPS satellites do not pass directly overhead, and as one approaches the poles, they do not rise above 45° above the horizon. This leads to a decrease in accuracy, especially vertical. Unlike GPS, the Russian GLONASS system, thanks to the peculiarities of its orbital constellation, provides a more stable signal and better accuracy in northern and polar regions.

All these factors emphasize that even the most advanced technology cannot fully replace critical thinking, observation, and the skipper's skills. Training that includes not only working with instruments but also understanding their limitations, as well as drills for actions in emergency situations (e.g., loss of GPS signal), becomes absolutely critical for safety at sea. The skipper must be able to "read" the sea and the sky, not just the chartplotter screen. The mention of jamming and spoofing, especially in the context of geopolitical conflict regions, directly links global events to safety and sailing trip planning. This is not an abstract threat, but a real problem that sailors must consider when choosing a route and preparing.

GPS: Safety and Efficiency in the World of Sailing

GPS, without a doubt, has significantly enhanced sailing safety and efficiency in the world of sailing, transforming it from a purely "romantic" and intuitive activity into a "smart," data-driven adventure.

How GPS enhances safety in sailing

- Precise position determination: GPS allows the skipper to accurately determine their location at any time of day and in any weather. This is critically important for navigation in challenging conditions, preventing collisions with other vessels or obstacles.

- "Man Over Board" (MOB) function: Many marine chartplotters and navigation applications have a dedicated MOB button or function. When activated, the system instantly saves the precise coordinates of where a person fell overboard and automatically plots a course back to that point. This significantly reduces search time and greatly increases the chances of a successful rescue.

- Geofencing: Modern marine GPS trackers allow setting virtual boundaries on the water. If a sailboat enters or leaves a specific zone, the owner receives a notification. This can be used for safety control (e.g., to avoid dangerous areas), preventing theft, or monitoring the movement of charter sailboats.

- Real-time vessel tracking: GPS tracking allows continuous monitoring of a vessel's location. This is important for the safety of the crew and cargo, as well as for the prompt response of rescue services in case of an incident.

- Integration with other systems: GPS data integrates with AIS (Automatic Identification System) and radar, providing the skipper with a comprehensive and up-to-date picture of marine traffic. This helps to detect other vessels in advance, assess collision risk, and make timely decisions. Another helpful resource for boaters is to understand yachting terminology.

- Access to weather information: Many marine GPS systems and applications provide access to up-to-date weather forecasts, tide, and current charts, allowing the skipper to make informed decisions, adjust the route, and ensure safer and more comfortable sailing.

Economic benefits of GPS and increased efficiency

- Route optimization: GPS allows skippers to plan the most efficient routes, choosing the shortest or safest paths, avoiding shallows and hazards. This reduces travel time and, consequently, costs. For example, route optimization using a GPS tracker can reduce distance and travel time by 14%. Another aspect to consider for optimal travel is whether to choose a catamaran or monohull.

- Reduced fuel consumption: More efficient route planning, precise speed control, and avoiding unnecessary maneuvers lead to a significant reduction in fuel consumption. This is especially relevant for motor yachts and for sailboats using an engine.

- Time saving: Accurate route planning and tracking, as well as the ability to avoid congestion, reduce overall travel time, which is particularly valuable in chartering.

- Insurance benefits: Some insurance companies provide discounts on sailboat insurance for those equipped with GPS trackers, as this reduces theft risks and facilitates searching in case of an incident.

Economic benefits (fuel savings, time savings, insurance) and significant safety improvements directly address the pain points of our target audience – fears of high cost and danger in sailing. GPS helps dispel these myths, making the dream of the sea more tangible and achievable. This emphasizes that modern technologies, when used correctly, can make sailing a hobby for a wide range of people, not just the elite.

A World Without GPS: Why Sailing Wouldn't Be the Same

Imagine a world where GPS suddenly ceases to exist. This would be a return to navigation of past centuries, when sailors relied solely on their skills and traditional instruments. The "world without GPS" scenario clearly demonstrates that the advent and widespread use of this technology has been a key catalyst for the development of mass sailing.

Consequences of GPS loss for sailing

- Sharp increase in risks: Navigation would become significantly more difficult and dangerous, especially in conditions of poor visibility (fog, rain), at night, or in unfamiliar waters. The risk of collisions and grounding would multiply.

- Full reliance on traditional methods: Sailors would have to rely entirely on skills in working with a compass, paper charts, bearings, dead reckoning (calculating distance traveled based on course and speed), and, for long passages, astronomical navigation (by stars, Sun, Moon).

- Increased demands on skippers and crew: Navigation without GPS would require much deeper and more refined knowledge and experience from skippers. Additionally, more people would be needed on board to perform navigation tasks that are now automated (e.g., one person taking bearings, another charting the course).

- Reduced accessibility of sailing: Sailing would likely again become the domain of a much smaller number of people – those willing to invest enormous amounts of time and effort in mastering complex traditional navigation skills. This contradicts the modern trend towards the accessibility of sea travel.

- Economic consequences: Increased travel time (due to less direct routes and the need for frequent stops to determine position), higher fuel consumption, increased insurance risks – all this would make chartering and owning a sailboat significantly more expensive. For more details on the practicalities, you might want to visit the Navi.training blog.

- Difficulties with search and rescue: Search and Rescue (SAR) operations would become much less effective and more prolonged without the ability to quickly determine the exact coordinates of a distressed vessel.

- Reduced comfort and freedom: The inability to easily and quickly determine location and plot a course would significantly reduce comfort and freedom of movement, turning every trip into a serious challenge.

The "world without GPS" scenario is a powerful and emotional way to show the reader why it's important not only to know how to use GPS but also to possess basic traditional navigation skills. If GPS didn't exist or disappeared, sailing would likely remain a niche activity for very experienced and highly qualified mariners. Its advent made sea travel accessible to a much wider audience. This enhances the value of GPS but also emphasizes that "accessibility" doesn't mean "no need for training," but rather "a change in the focus of training." This approach prepares skippers for any conditions, making them truly competent and confident.

Final Thoughts: Your Path to Confident Sailing with Navi.training

GPS is, without a doubt, an incredible tool that has revolutionized the world of sailing, making it safer, more accessible, and more efficient. It has become an indispensable assistant for every skipper. Understanding how GPS works is fundamental for confident navigation.

Navi.training offers support and training in Russian, Ukrainian, and English. This eliminates language barriers, making the learning process as comfortable and understandable as possible, allowing you to focus on what matters. Real confidence and competence only come with practice, and Navi.training offers unique practical sessions, including night navigation and maneuvers, that prepare students for any conditions and scenarios, giving them invaluable experience beyond the basic course.

Navi.training instructors are not just theorists, but experienced sailors and professionals who share their real-world experience, knowledge, and passion for the sea, ensuring a personalized approach and support. The school does not leave its graduates to face the world of sailing alone after obtaining their certifications. Navi.training provides support and assistance with booking sailboats for independent voyages, making the transition from training to your first charter as smooth and carefree as possible. For those looking to learn more about certifications, exploring the different types of boat licences can be beneficial.

Navi.training makes learning safe, structured, and achievable even for those starting "from scratch," dispelling myths about the complexity and high cost of sailing. It's a path from dream to helm, where every step is supported by experts, and safety and confidence become an integral part of your sea adventure. For those interested in deeper insights, the yachting school provides comprehensive programs covering various aspects of sailing, including different types of sailing yachts and yacht etiquette.