Many beginners, just dreaming of the helm, are frightened by the seeming complexity of seamanship. Questions about choosing an anchor, chains, proper anchoring techniques, and staying at anchor can seem like an insurmountable obstacle. "It's too complicated," "it's for experienced sailors," "I'll never figure it out" – such thoughts often stop them on the path to their dream. But we hasten to assure you: archiving, like what is yachting in general, is absolutely learnable. With the right knowledge and a little practice, the initial trepidation gives way to confidence and enjoyment of the process. This article is your first detailed guide, where we will look at the types of anchors on a sailing yacht. Together, we will understand what they are, how to choose and use them, so that your sailing holiday is not only exciting but also safe. Anchoring is an important and very interesting stage on the way to independently managing a yacht, and we will help you take this step. After all, the path to any skill begins with quality training, where even the most complex things are explained simply and clearly.

If you are just starting, we recommend looking into other materials on the topic of Yachting for Beginners.

Why an anchor on a yacht: more than just a "parking brake"

So, what is an anchor on a sailing yacht really for? At first glance, the answer is obvious – to stop. But its functions are much broader and more important than those of a simple car "parking brake." An anchor is a fundamental element of safety at sea and the autonomy of any vessel at sea. Its main task is to reliably hold the yacht in place when not underway, effectively counteracting the forces of wind and current. This is not passive "parking," but an active provision of safety, especially when the weather starts to change.

It is the anchor that gives the skipper freedom of choice. Thanks to it, you can stop in the most picturesque and secluded coves, inaccessible by land and where there are no equipped berths or mooring buoys, which require knowledge of various mooring types. This opens up completely new horizons for travel, allowing you to enjoy untouched nature and tranquility. Psychologically, the confidence that your anchor is holding securely is the key to a peaceful rest. The fear that the yacht will drag and be carried onto rocks or other vessels disappears, and you can truly relax and enjoy the moment. The ability to correctly choose a place for an anchorage, properly deploy the anchor, carefully check how well it has "set" in the seabed, and calmly spend the night or several days is one of the key skills of a truly competent skipper. Understanding the principles of operation of the entire anchoring system instills confidence and allows you to get maximum pleasure from yachting without unnecessary stress. In addition, an anchor can be used for short stops, for example, for swimming or lunch in a beautiful place (sometimes such an anchor is called a "lunch hook"), or even to assist in maneuvering in difficult situations, although these are more advanced techniques. Thus, an anchor is not just a heavy piece of metal on a chain, but your active tool for managing freedom, safety, and comfort on a sea journey.

Two captains on the bridge, two anchors on board: primary and secondary anchor

Experienced sailors know: at sea, it is always better to have a backup plan. This rule fully applies to anchors. On board a modern sailing yacht, especially when it comes to cruising, there should usually be at least two anchors: a primary (also called a bower anchor) and a secondary (or auxiliary, often called a kedge anchor). This is not a whim or an extravagance, but a requirement of good seamanship and, in many cases, insurance companies and classification societies.

The primary anchor is your main "working tool." It is usually heavier and more powerful than the secondary anchor, and it is the one you will use in 99% of cases for anchoring overnight or for an extended stay. It is installed on the bow of the yacht in a special device – an anchor roller, which ensures convenient deployment and retrieval using an anchor windlass. The secondary anchor plays the role of "plan B." It is necessary in case of loss or damage to the primary anchor – a rare but possible situation. In addition, the secondary anchor can be useful in a number of other situations:

- For setting two anchors (e.g., bow and stern, or two anchors from the bow at an angle) to reduce the yacht's yawing (swinging) at anchor in strong winds or currents, or in very confined waters.

- To help refloat a grounded yacht (so-called kedging).

- As a temporary anchor during certain maneuvers.

A secondary anchor is not ballast that just lies in a locker. It is your insurance and an additional tool that can be invaluable in a difficult moment. It is important that it is always ready for immediate use. This means that it must not only be correctly selected but also equipped with its own anchor rode (usually a short length of chain and a long rope) and stored in an easily accessible place. If the secondary anchor is difficult to reach or not ready for quick deployment, it may be useless in an emergency.

Choosing the main anchor: types of anchors for yachts, materials, and selecting an anchor for a yacht (anchor weight for a yacht)

Choosing the primary anchor is a responsible task, as the safety of your yacht and the peace of mind of the crew directly depend on its reliability. The modern market offers many designs, representing various types of anchors, each with its own features, advantages, and disadvantages depending on the type of seabed and anchoring conditions.

Popular types of anchors for yachts:

- Plow-type anchors:

- CQR (Coastal Quick Release): A classic hinged shank anchor that has proven itself well on sandy and muddy bottoms. However, it can "plow" the bottom during strong jerks and is not always reliable on hard rocky bottoms or in dense seaweed. It is considered somewhat outdated.

- Delta: An improved version of the plow, but without a hinge. Thanks to its weighted tip, it digs deeper and faster into the seabed. It works well on most types of seabed, except, perhaps, very dense seagrass beds. Very popular on charter yachts.

- Claw-type anchors:

- Bruce: This claw-like anchor grips soft and medium-soft bottoms (sand, mud) well and quickly. However, its holding power on hard bottoms may be insufficient. In terms of its characteristics, it is somewhat inferior to more modern designs.

- Fluke-type anchors:

- Danforth: A lightweight and compact anchor with two flat, pointed flukes. It has high holding power per unit of weight, especially on soft or medium-soft bottoms (firm sand, mud). However, it may not penetrate very hard surfaces well or may slide over dense seaweed. Due to its compactness when folded and light weight, it is often used as a secondary anchor.

- New generation anchors:

- Rocna, Spade, Mantus, Vulcan, Ultra, and others: These are modern developments characterized by advanced geometry, the ability to set quickly and dig deep, and high holding power on a wide variety of seabed types, including challenging ones. Many of them (e.g., Rocna, Mantus, Spade) are equipped with a special roll-bar that helps the anchor orient correctly when it hits the bottom and ensures quick setting. The Vulcan anchor (a modification of the Rocna) is designed without a roll-bar for better compatibility with some bow roller designs, especially on motor yachts. These types of anchors are considered among the most effective today, but they are also more expensive than classic models.

- Fisherman/Admiralty anchor: This is the "classic" anchor from pictures, with a transverse stock and two arms/flukes. It holds well on rocky bottoms and in seaweed, as its flukes can catch on irregularities or penetrate a layer of vegetation. However, for modern sailing yachts, it is too heavy and cumbersome, and on soft bottoms, its holding power per unit of weight is inferior to many modern designs.

Anchor materials:

- Galvanized steel: The most common option due to its good combination of strength and affordable price. Hot-dip galvanizing provides corrosion protection for many years.

- Stainless steel (usually AISI 316 or 316L): Looks very impressive and has excellent corrosion resistance. However, such anchors are significantly more expensive and, for the same cross-section, may be slightly less strong in terms of tensile strength than some high-strength galvanized steels.

- Aluminum alloys: Anchors made of special aluminum-magnesium alloys (e.g., Fortress or some Spade models) are notable for their light weight combined with very high holding power, especially on soft bottoms. They also have excellent corrosion resistance. Often, such anchors have a disassemblable design, which is convenient for storage, and are therefore popular as secondary or storm anchors.

Selecting an anchor for a yacht using manufacturer tables:

Anchor manufacturers (such as Rocna, Spade, Mantus, Lewmar, etc.) provide detailed tables in which the recommended anchor weight for a yacht or anchor model is correlated with the length and/or displacement (full load) of the yacht. These tables are a good starting point. However, it is important to remember that in addition to length and displacement, the force with which wind and waves will act on an anchored yacht is significantly influenced by its sail area and windage (freeboard height, superstructure shape, presence of awnings and other equipment on deck). For yachts with a large sail area or high profile (e.g., many catamarans), an anchor one or two sizes larger than indicated in the standard table for a monohull yacht of the same length or displacement may be required. Some manufacturers already take this into account in their recommendations or offer separate tables for multihull vessels. Considering all these factors allows for the correct selection of an anchor for a yacht. Here is a simplified example of what an anchor selection table might look like. Remember that this is only an illustration, and it is always necessary to consult the official recommendations of the specific anchor manufacturer for your yacht model and intended sailing conditions.

| Yacht Length (m) | Full Displacement (t) | Approx. Delta Anchor Weight (kg) | Approx. Rocna/Vulcan Anchor Weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8-10 | 3-5 | 10-16 | 10-15 |

| 10-12 | 5-8 | 16-20 | 15-20 |

| 12-14 | 8-12 | 20-25 | 20-25 |

Note on the table: The data are indicative and may vary depending on the specific anchor model and operating conditions. Always consult the manufacturer's official recommendations. The anchor weight for a yacht is critical for reliable anchoring.

It should be understood that there is no absolutely "universal" anchor that works perfectly on any seabed. However, modern designs, especially new generation anchors, strive for greater versatility and reliability in a wide range of conditions compared to older types. Although they may be more expensive, such an investment is often justified by increased safety and your peace of mind, especially if you are planning family trips or voyages to areas with diverse anchoring conditions.

Anchor Rode: anchor chain, rope, or a combination? Anchoring system in detail.

The anchor rode is what connects the anchor to your yacht. How well the anchor holds depends directly on its correct choice, condition, and length. The anchor rode can consist entirely of anchor chain, entirely of rope (which is rare for the primary anchor on cruising yachts), or, most commonly for secondary anchors, a combination of chain and rope.

Chain for the primary anchor: length, caliber, and compatibility (anchor chain)

For the primary, or bower, anchor on a cruising sailing yacht, an all-chain anchor rode is today's de-facto standard. And there are good reasons for this. A proper anchor chain is key to success.

- Chain length: One of the most important parameters is sufficient chain length. For reliable anchoring in various conditions and at different depths, it is recommended to have at least 70-80 meters of chain on board. Why so much? A long chain not only allows anchoring at greater depths but also creates the so-called catenary effect – the sag of the chain between the yacht and the anchor. This sag acts as a powerful shock absorber, softening jerks from waves and gusts of wind, and, most importantly, ensures a more horizontal pull on the anchor, causing it to dig deeper into the seabed and hold better. This significantly increases the reliability of the anchorage and comfort on board.

- The key concept here is "scope" – this is the ratio of the length of deployed anchor rode (from the bow roller to the anchor) to the total depth (depth under the keel plus the height of the bow roller above the water). For calm weather and reliable holding ground, the minimum scope is 3:1 (but this is usually insufficient for overnight stays), for normal conditions 5:1 is recommended, and in strong winds (especially if katabatic winds are expected), swell, or on not very reliable ground – 7:1 or even more. With a chain length of 70-80 meters, you can ensure sufficient scope at most anchorages.

- Chain thickness (caliber): The choice of chain caliber depends on the size and displacement of your yacht, as well as the recommendations of the anchor and yacht manufacturers. Common calibers for yachts 10-15 meters long are 8 mm, 10 mm, or 12 mm.

- It is critically important that the caliber and standard of the chain precisely match the gypsy (special drum) of your anchor windlass. There are different chain calibration standards, the most common in Europe being DIN 766 and ISO 4565. Even chains of the same nominal caliber (e.g., 10 mm) can have slight differences in link geometry depending on the standard (e.g., DIN 766 P28 or P30). Using an incompatible chain will lead to it slipping or jamming in the windlass, which is not only inconvenient but also dangerous, and can also damage the expensive mechanism. Replacing a windlass due to an incorrectly chosen chain is a very costly undertaking.

- When choosing chain thickness, weight limitations must also be considered. A chain that is too thick and heavy significantly increases the weight in the bow of the yacht, which can negatively affect its performance characteristics, especially in waves, and disrupt the overall balance. Therefore, a reasonable compromise between necessary strength and weight is sought here. Sometimes, to reduce weight while maintaining strength, higher strength grade chains (e.g., G40 or G70 instead of the standard G30) are used, which can withstand greater loads for the same link diameter.

- Chain materials:

- Galvanized steel: The most common choice. Hot-dip galvanizing provides good corrosion protection. Chains come in different strength grades (G30, G40 (HT), G70). G40 (High Test) is popular for cruising yachts as a good balance of strength and weight.

- Stainless steel (AISI 316): Very durable, does not rust, and looks beautiful, but is significantly more expensive than galvanized.

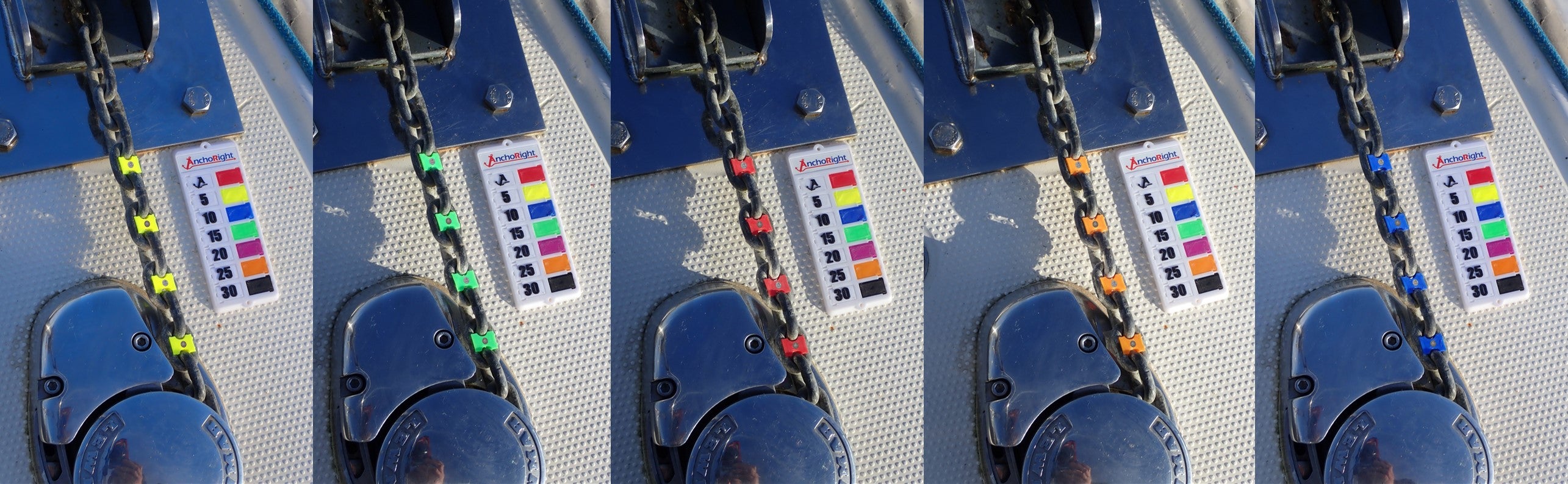

- Chain marking: To easily determine how much chain has been deployed, it must be marked. This is done using special colored plastic inserts in the links, painting the links, or using colored cable ties. Usually, every 5 or 10 meters (or 25 feet) are marked. Standard color schemes exist, for example, the sequence: red – yellow – blue – white – orange, repeated for each subsequent segment. Knowing how much chain is overboard is absolutely essential for proper and safe anchoring.

Combination rode for the secondary anchor:

For the secondary anchor, a combination anchor rode is often used: 5-10 meters of appropriately sized chain connected to a strong anchor rope (usually nylon).

- The length of chain near the anchor serves several functions: its weight helps the anchor to position correctly on the seabed and begin to dig in, and it also protects the main, more vulnerable part of the rode (the rope) from chafing on rocks or shells on the bottom.

- The anchor rope (line) is usually made of nylon (polyamide). Nylon has good strength and, very importantly, elasticity – it can stretch under load, absorbing jerks from waves and wind. Both three-strand (twisted) and plaited (e.g., eight-plait) ropes are used. Three-strand rope is easier to splice to chain, while plaited rope is more flexible and less prone to kinking and twisting. The length of the rope should be sufficient to ensure the necessary scope in the intended areas of use for the secondary anchor (usually 30-50 meters or more).

Connecting chain and rope: A reliable connection between the chain segment and the rope is crucial to ensure your secondary anchor doesn't fail when needed.

- Splice (eye splice to chain): Considered the most reliable and correct method, especially if the connection needs to pass through a roller or windlass gypsy (although this is less relevant for a secondary anchor). The rope is spliced directly into the last link of the chain, often using a thimble (a metal or plastic insert to protect the rope from chafe).

- Shackle: A simpler method, but it's important to use a quality stainless or galvanized steel shackle that matches the strength of the chain and rope. The shackle pin must be securely moused with wire or a special retainer to prevent it from unscrewing due to vibrations.

Secondary Anchor: Your Reliable Helper in Special Situations

As we've already mentioned, the secondary anchor (kedge) is not just ballast, but an important element of safety and a versatile tool on board. Its selection, rigging, and storage should be approached with no less responsibility than that of the primary anchor.

Choosing the type and material for the secondary anchor:

Since the secondary anchor is most often stored in a locker or other confined space and is not used as frequently as the primary, qualities such as lightness, compactness, and a high holding power-to-weight ratio come to the fore when choosing it. Various types of anchors can be used as secondary anchors.

- Fortress (aluminum alloy): One of the most popular choices for a secondary or storm anchor. These anchors are exceptionally light (significantly lighter than steel counterparts of the same holding power) and have phenomenal holding power, especially on soft bottoms (sand, mud). They often have a disassemblable design, which is very convenient for storage. Some Fortress models allow adjustment of the fluke angle (e.g., 32° for hard sand and 45° for very soft mud), which increases their effectiveness on different types of seabed.

- Danforth (steel, galvanized): Also a good option due to its lightness, compactness when folded, and good holding power on sand and mud. It is generally more affordable than a Fortress.

- Grapnel anchor: Foldable and very compact, but its holding power on most bottoms is low. It can be useful for very small boats, dinghies (tenders), or for temporarily hooking onto rocks or snags, but is not recommended as the primary secondary anchor for a cruising sailing yacht.

The lightness and disassemblability of a secondary anchor are not just conveniences. In an emergency, when you need to quickly deploy a second anchor (e.g., if the primary anchor is dragging and you are drifting towards an obstruction), the ability to easily and quickly retrieve, assemble (if it's disassemblable), and prepare it for deployment by one or two crew members can be crucial. A heavy and cumbersome secondary anchor that is difficult to extract from a locker can be useless precisely when it is needed most.

Rigging and storing the secondary anchor:

The secondary anchor must always be ready for immediate use.

- Storage: It is usually stored in an easily accessible locker (e.g., in the cockpit or bow), a dedicated anchor locker, or on a deck mounting (e.g., on the railing/pulpit). It is important that it is securely fastened and cannot shift spontaneously during pitching or rolling.

- Rigging: As mentioned, typical rigging for a secondary anchor is 5-7 meters (sometimes up to 10 meters) of appropriately sized chain, connected to a strong nylon anchor rope at least 30-50 meters long (and preferably longer, depending on the anticipated depths of use).

- The anchor rope should be neatly coiled (flaked) and secured so that it can be quickly deployed without risk of tangling. The bitter end of the rope (the end that remains on the yacht) must be securely fastened on board.

Anchoring System: Windlass, Snubber, and Other Important Details

In addition to the anchor itself and the anchor rode, the anchoring system of a modern sailing yacht includes several other important elements that ensure the convenience, safety, and durability of the entire system.

- Anchor Windlass (capstan or windlass): This is a mechanism designed for deploying and especially retrieving the anchor and anchor chain. Modern cruising yachts are most often equipped with electric windlasses, although manual ones may be used on smaller vessels or as a backup system. Understanding the operation of the anchoring system is essential for a skipper.

- Chain Compatibility: We have already emphasized, and it is worth repeating – the windlass gypsy must be strictly designed for the caliber and standard of your anchor chain. Attempting to use an incompatible chain can lead to its damage, windlass failure, or the inability to securely hold the chain. Replacing the windlass or its gypsy is an expensive pleasure, so this issue requires the utmost attention when buying a yacht or replacing the chain.

- Chain Stopper/Compressor: This is a special device installed on deck between the anchor roller and the windlass. Its task is to grip the anchor chain and take the main load from the tensioned anchor rode during anchoring. This relieves the load from the windlass itself (its brake and gearbox), extending its service life and preventing damage during strong jerks.

- Anchor Snubber or Bridle: This is an indispensable device for comfortable and safe anchoring, especially with an all-chain rode.

- Purpose: An anchor snubber (often called by its English name "snubber" for monohulls or "bridle" for catamarans) is a strong elastic rope (usually nylon) that is attached at one end (or via a hook) to the anchor chain, and at the other end (or two other ends) – to strong cleats on the bow of the yacht. After its installation, the anchor chain is paid out slightly so that the main load from the anchor is taken by the snubber, not by the windlass or roller.

- Advantages of using an anchor snubber/bridle:

- Reduced Jerking: The elastic rope of the snubber dampens sharp jerks caused by gusts of wind or waves, making centering significantly more comfortable.

- Noise Reduction: Unpleasant noise from the friction of a taut chain in the roller or its clanking is eliminated or significantly reduced.

- Equipment Protection: Constant load is removed from the anchor windlass, its brake and gearbox, as well as from the bow roller, which extends their service life.

- Increased Anchoring Reliability: The snubber helps the anchor to hold better in the ground, as it prevents sharp jerking forces that could dislodge it.

- For a monohull yacht (snubber): This is usually one or two lengths of strong nylon rope, equipped with a special chain hook or other device (e.g., a devil's claw, or a plate-type grab). The free ends of the rope are led to bow cleats.

- For a catamaran (anchor bridle): Due to the two hulls and often higher bridge deck, catamarans use a Y-shaped system of two ropes (bridle legs), which are attached to strong points on each of the hulls (usually to bow cleats or special pad eyes). Where the bridle legs meet, they are connected to the anchor chain using a hook or a strong soft shackle. Such a system ensures even load distribution between the hulls, significantly reduces catamaran yawing at anchor, and increases comfort.

An anchor snubber/bridle is not a luxury, but an absolutely necessary element for comfortable and safe anchoring. Its use significantly improves the quality of life on board while at anchor and protects expensive anchoring equipment.

- Securing the Bitter End of the Chain: The bitter end of the anchor chain (the one that is in the chain locker and is not paid out overboard) must be securely fastened to a strong structure inside the yacht's hull, usually in the chain locker. This prevents the accidental loss of the entire anchor chain along with the anchor if, for some reason, its entire length is paid out. However, it is important that this fastening is such that in an extreme emergency (e.g., if the anchor is firmly stuck and the yacht is in danger), the bitter end can be quickly released and the entire chain jettisoned. For this, special joining links or pelican hooks are sometimes used. This is often forgotten, but the correct and well-thought-out securing of the bitter end of the chain is a hidden but very important element of the overall safety of the anchoring system.

Safe Anchoring: Calculating Scope, How to Anchor a Yacht, and a Peaceful Sleep

The ability to safely and reliably anchor a yacht is an art based on knowledge, experience, and attention to detail. It's not just about dropping the anchor overboard; it's a whole process that begins long before approaching the anchorage and continues the entire time you are at anchor. This is what proper anchoring is all about.

Calculating the required length of anchor rode (scope calculation):

As we've already mentioned, scope is the ratio of the length of the deployed anchor rode (L) to the depth (H), where H is the sum of the water depth according to the echo sounder and the height of your bow roller above the water (freeboard at bow). Correct scope calculation is critical.

- Formula: Scope = L/H.

- Recommended values:

- 3:1 – only for short-term stops in very calm weather and on absolutely reliable holding ground. Not recommended for overnight stays or if there is the slightest doubt about the weather.

- 5:1 – standard scope for normal conditions and good holding ground.

- 7:1 and more – in strong winds, on not very reliable ground, if worsening weather is forecast, or if you want to sleep particularly peacefully.

For example, if the depth is 10 meters and the bow roller height is 1 meter (total H = 11 meters), then for a scope of 5:1 you need to deploy 11 × 5 = 55 meters of chain.

Anchor Lights and Shapes:

According to the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs), an anchored yacht must display:

- At night: One all-round white light, visible from all directions, in the most conspicuous place (usually at the masthead or on a special flagstaff at the bow). Yachts over 50 meters in length display two such lights.

- By day: One black ball, also in the most conspicuous place.

Failure to comply with these requirements is not only dangerous (other vessels may not see you or may misjudge the situation) but is also a violation of the rules.

Common beginner mistakes and how to avoid them (how to anchor a yacht):

- Insufficient scope: The most common mistake. Skimping on chain length leads to poor anchor holding.

- Incorrect choice of location: Anchoring on poor holding ground, without protection from wind and waves. This affects how to anchor a yacht safely.

- Not checking that the anchor has "set": Simply dropping the anchor and assuming all is well.

- Paying out the chain too quickly: The chain piles up on the anchor.

- Ignoring the yachting weather forecast: Anchoring in calm weather, only for a storm to arrive at night for which you are unprepared.

- Forgetting to turn on the anchor light or display the black ball.

- Underestimating your yacht's swinging circle and that of neighboring vessels: Anchoring too close to other vessels or obstructions.

Technologies such as GPS plotters, echo sounders, and special "anchor alarm" apps on smartphones or chartplotters are excellent aids for the modern skipper. They help to accurately determine depth, seabed characteristics (some echo sounders), location, and monitor whether the yacht is dragging anchor. However, they do not replace fundamental skipper knowledge and skills: the ability to read a nautical chart, assess the situation visually, understand the weather forecast, and "feel" your boat. Technology is a tool in the skipper's hands, not an autopilot for anchoring. Proper use of technology helps understand how to anchor a yacht most effectively. For the most complete and up-to-date information on yachting training standards, including safe anchoring methods, you can refer to the resources of international sailing organizations, for example, to the official website of ISSA. Schools accredited by ISSA adhere to high standards in skipper training.

From Theory to Practice: How Navi.training Will Help You Become an Anchoring Master

The theoretical knowledge you have gained from this article is an important foundation in general sailing theory.

Enroll in our yachting school, where you will gain practical skills from experienced instructors.

By studying at Navi.training, you get:

- Knowledge and experience from professionals: Our instructors are not just certificate holders, but experienced yachtsmen with thousands of nautical miles sailed and a wealth of practical anchoring experience in the most diverse corners of the world and in various conditions. They will share with you those practical nuances and "seafaring tips" that cannot be found in any textbook.

- Training in your native language: We conduct training in Russian, Ukrainian, and English. This is especially important when mastering such technically rich topics as anchoring. The ability to freely ask questions, discuss complex moments, and receive comprehensive answers in an understandable language is not just comfort, but a guarantee of a deep understanding of the material and, consequently, your future safety.

- Emphasis on safety: Safety is our absolute priority. All training programs and practical sessions are imbued with a culture of safe seamanship. Proper and reliable anchoring is one of its most important aspects.

- International ISSA certificate: Upon successful completion of the course and passing the exams, you will receive an internationally recognized ISSA Certification – one of the authoritative types of Yacht license. Confident mastery of all aspects of anchoring, including equipment selection and actions in difficult conditions, is an integral part of the requirements for a competent skipper of this level.

Also, check out the yacht charter offer for those who want to enjoy a holiday on the water without the hassle.

An anchor is not just a piece of metal at the end of a chain. It is a complex system that requires understanding, and an important skill that opens the doors to the true freedom of sea travel, to seclusion in the most beautiful coves, and to those unforgettable moments for which we go to sea. To master the art of anchoring means to obtain one of the main keys to the world of independent yachting, to those hidden corners of the planet that are accessible only from the water. The path from a timid dream of "going to sea under sail" to confidently managing your own or a chartered yacht, to independent anchorages in the azure bays of the Mediterranean or the rugged fjords of Norway – is absolutely real and achievable for everyone. The Navi.training sailing school was created precisely to help you navigate this fascinating path – safely, effectively, and with pleasure. We don't just teach you to pass exams for a certificate; we prepare truly competent, thinking, and confident skippers capable of making independent decisions and enjoying every moment of their sea adventure. Knowledge of various types of anchors and the ability to work with them is part of this preparation. Ready to drop anchor in a world of new knowledge and impressions? Learn more about our yachting courses, such as the Inshore Skipper Sail course, on the Navi.training website and take the first step towards your maritime dream today! With us, you will master all the intricacies of yachting, including the art of selecting, using, and maintaining anchoring equipment, in your native language with experienced instructors. You will receive unique practical training day and night, an internationally recognized certificate (an important element for those seeking skipper certificates), and our comprehensive support even after graduation, including assistance in organizing your first independent charter. Navi.training – your reliable pilot from dream to helm!